Background #

This is the story of a case I worked a long time ago. At the time I was working in an infrastructure development team. We had a VMWare vCenter 5.5 cluster that started as a prototype, but soon became mission critical (as is the way for those systems sometime). Other than overutilising the hardware with random VMs it had been functioning seemlessly with no issues for a long time, and then developed an interesting fault. The vCenter cluster would disconnect from the storage multiple times an hour.

This meant that people who were using the VMs would be disconnected from them until the cluster network connectivity was restored, read and write events were lost and a great deal more. It wasn’t great, and was incredible noticable to our users using it.

Initial Investigation #

My first port of call was to review the documentation. It was thorough including everything from cabelling diagrams, configurations, and so much more, but an interesting thing that caught my attention was one chapter labelled “future additions”, it talked about how they planned on adding future additions including routing protocols.

This was my first shock, firstly the date of the future addition was a few years prior (clearly identifying it as never happening), and up until this point I was suspected a link failing over causing OSPF to reconverge the network (and a minor outage in the mean time). But the second shock was logging into the first switch and discovering it was entirely a layer 2 switched network.

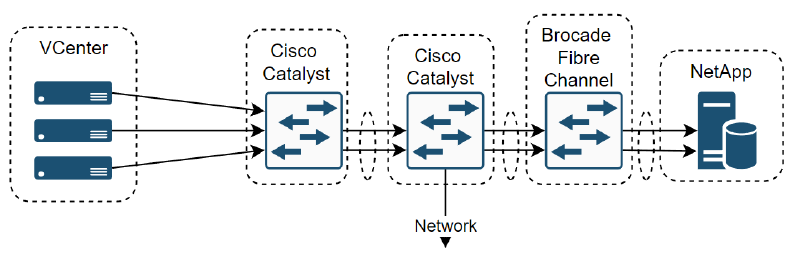

At a simple layer the network looked like this, comprised of some HP Enterprise servers for the vCenter cluster (suspected Gen 7), Cisco Catalyst switches (suspected 3750G), and Brocade Fibre Channel Switches:

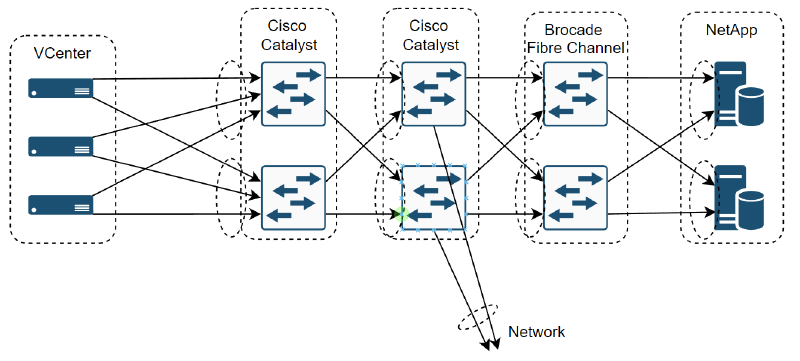

So I re-evaluated my initial assessment, and thought it’d be a simple Spanning Tree Protocol (STP) problem. I connected to the first hop switches away from the vCenter servers and quickly realised that this network was much more complex than I realised. The network was built for high availability, this meant that there was 3 ESX servers to form the vCenter cluster, Cisco switches stacked together to form a single switch, same with the Brocades, two NetApp network attached storage that were duplicating one another and they were all wired together with trunked port channels, spanning the devices.

The other thing was that it was fibre channel network, which makes sense when dealing with storage, but was not something I had necessarily experienced before. This meant the actual network looked something more like this:

So now the complexity was starting to increase, but this complexity was there to ensure the high availability. Did that mean there was multiple failures? Spanning tree causing chaos through blocking port channels across stacked switches?

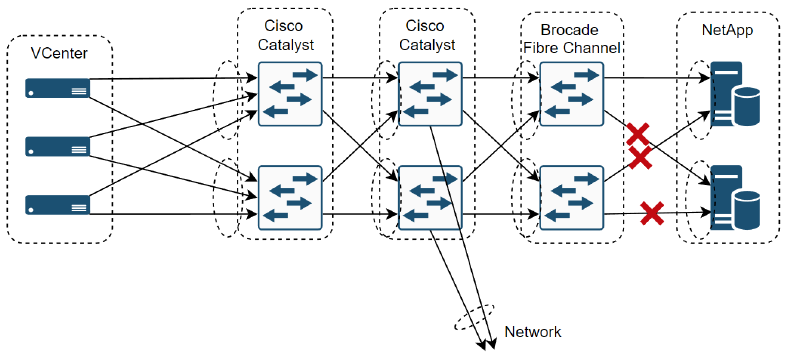

Fault Finding #

The approach I took was to start by finding which links exactly flapping. Going switch by switch I checked and validated the configuration as well as monitoring the link status until it eventually disconnected. That lead me to finding the culprit, which was itself the connection between the Brocade fibre channel switches and the NetApp storage. It was just as I had suspected though, it wasn’t a single fault, it was 3 at once, and eventually when the 4th link failed the entire storage array would go offline and take the vCenter cluster with it.

Because this was a switched network, there weren’t too many layers to work with, but as there was only the logical link layer and hardware layer it was a matter of working through those. This involved:

- Reviewing the configuration for a fibre channel misconfiguration

- Reviewing the configuration for an Jumbo Frames/MTU misconfiguration

- Checking Link Aggregation Control Protocol (LACP) was running successfully

- Monitoring Spanning Tree Protocol for changes in topology

- Monitored Hot Standby Router Protocol (HSRP) in case the stacked devices were fighting over who was master

- Updating each device to the latest firmware version (this included the cisco and brocade switches, the HPE servers, and the NetApp storage arrays)

- Checked each Small form-factor pluggable (SFP) interface for hardware faults and wiring misconfigurations

Uncovering some oddities #

During this investigation a few oddities were uncovered, we found a lot of cables connected which weren’t in the original documentation. Tracing each back to the source revealed some that shouldn’t have been connected, and some that were part of a project that had been stood up since and was supposed to be connected.

The other oddity that stood out was that the SFP interfaces that connected the Cisco Switches to the Brocades used Brocade SFP modules. I had seen in the past with F5 devices that their SFPs had a custom MTU for sending bigger traffic than the standard. Working my way through pages of cisco documentation I eventually uncovered an undocumented command: service unsupported-transceiver, which allowed the devices to handle 3rd party SFPs.

Actually Fixing It #

Even after rectifying these issues though, we still were encountering the issue, and less calmer minds were talking of a full rebuild of the system, which would involve taking a mission critical system offline for months. That wasn’t necessarily a solution I can live with.

For one final hail mary I asked it I could take two of our spare Cisco switches and replace the Brocades with them, connect them up and see if that fixes it. If not, then I’d concede and start work on the replacement.

We had a couple of space Cisco Nexus devices (either a 6k or 9k series) so scheduled a time after hours. We meticulously planned the details. We’d disconnect the vCenter cluster from the storage, unplug and switch the Brocades with the new Cisco Nexus devices, apply our pre-written configurations, ensure network connectivity and then slowly bring up the vCenter again, reconnecting it to the NetApp storage system and then monitor.

That’s exactly what we did in one after, running back and forth to the Datacentre to make a couple of minor amendments, and some minor changes to the Cisco configuration and then the nerve wrecking time as we waited to see if the issue would appear.

Conclusion #

The switchover was a success, we now had a converged network with all links up. 30 minutes went by, and still no failover, after an hour we still had not seen any link flapping or outages. At the 2 hour mark we were feeling pretty confident we had resolved the entire issue so congratulated each other and called it a day. Coming into the office on Monday felt great as we still hadn’t seen any outages and people could reeturn to the mission critical work they were doing.

I’m still not entirely sure what the fault was, realistically it probably reflected the poor monitoring of the device health (as I doubt both failed at the same time). Now days those systems have probably been long replaced, and replaced with lessons learned from Site Reliability Engineering (SRE), to ensure that it’s actually high availability. Never the less it’s still an interesting to reflect on some of the technical challenges we face and overcome, especially prominent ones that stick in ones mind.

TL;DR - Complex High Availability Layer 2 Network suffers odd issue, working through every possibility leaves the only culprit left the devices themselves, replacing them leads to success and the converged high availability network staying up forever more.